I suggest that these references may appear relatively natural within the framework of U.S. patriotic rhetoric, but that within the configuration of events at the time the statements were made (from the aftermath of 9/11 to the 2004 campaign for the presidency), the president has wrung words out of their religious context to serve non-religious interests.

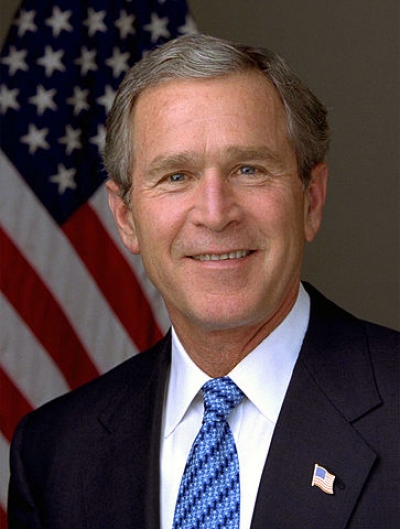

It has been said that President (George W.) Bush used religious language more than any president in U.S. history. I have no statistics to support this (the Baptist Jimmy Carter was fairly lavish with religious references too), but it is a fact that (especially after September 11th) both Bush's speeches and other off-the-cuff remarks make frequent allusion to God, Scripture and other religious texts.

If we read 'with' rather than 'against' the text, this is not totally unexpected and not necessarily immoral. Patriotism with a religious flavor is part of the general American ideology: ‘basically, the U.S. are a diffuse form of theocracy’ — not in the sense of being led by a caste of clergy, but in the sense of believing that its fate and mission are determined by divine providence — a 'theocracy' which inspired George H. Bush (Sr.) to start his inaugural address with a prayer asking God to 'Make us strong to do your work, willing to hear and heed your will,' and his son George W. Bush to say that 'we are guided by a power larger than ourselves who creates us equal in his image' and to talk of a 'calling' by 'Him', who 'fills time and eternity with His purpose [which] is achieved in our duty'. George W. Bush's autobiography (1999) is titled A Charge to Keep, a phrase from Charles Wesley):

A Charge to keep I have / A God to glorify, / A never-dying soul to save / And fit it for the sky / To serve the present age, / My calling to fulfill: / O may it all my powers engage / To do my Master's will!

Bush viewed his own presidency as part of a divine plan. He has been reported as saying, 'I believe God wants me to be president' (note the 'I believe', which constitutes no external evidence). The idea of a 'calling' is a Lutheran idea (the Christian is called to involvement in the world, rather than to withdrawal into a life of contemplation, with the additional component of the individual's responsibility to make the world a better, kinder place. Charles Wesley's hymn was inspired by Leviticus 8:35, 'Keep the charge of the Lord, that ye die not'; but note that in the hymn the 'charge' is 'a God to glorify' – not to 'do everything we can to protect the American homeland', as Bush defined his mission.

The idea of election is Calvinist in nature, and has throughout history been appropriated by various groups and nations – unsurprisingly, always to include themselves among God’s chosen ones and reprove others. After Sept. 11, Bush (rather immodestly) declared that 'this call of history has come to the right country' and talked of himself as 'being chosen by the grace of God to lead at that moment'. Obviously there is neither objective nor scriptural evidence for the election of the U.S. or for the choice of George Bush as the instrument of God's purpose; nor, a fortiori, for the assimilation of the Master's Will to the global strategy of the US: that is a heavily skewed reading of reality as circumstantial evidence, albeit a recurrent one in American history. It suggests (but does not argue) a divine sanction of the presidential powers: if the US feels invested with a divine mission to tell 'the captives 'come out' and to those in darkness 'be free' (Isaiah 49:9) or to 'defend the hopes of all mankind' (Bush, State of the Union 2003) it is implied that those who question Bush's foreign policy are no longer critics, but blasphemers.

The Methodist George Bush might, of course, have been talking 'in good faith'; I have no right to question that. He declared his initial programme to be one of compassion, charity, and humility, based on the idea that 'everyone belongs and everyone deserves a chance' (Bush, Inaugural Address). This might be viewed as a secular translation of Wesley's idea of universal grace, but at least one critic suggested that 'compassionate conservatism' was tantamount to offering the poor and the disempowered religion instead of the political power or economic resources they needed. What is disturbing, indeed, is how this discourse with its religious resonances was made to tie in with, or put to the service of strategic, corporate and electoral interests.

As George Monbiot put it, 'a moral case is not the same as a moral reason: (...) superpowers act out of self-interest, not morality, and the US in Iraq is no different'. U.S. troops would not be fighting in the region if it were the world's leading producer of pudding rather than the repository of the world's largest oil reserves. But the moral case must be made. 'The genius of the hawks has been to accept a fiction as the reference point for debate'. The deconstruction of this fiction is where the toolkit of CDA may come in useful.

A first point, already mentioned in passing, is the tendency to reduce complex issues to simple binary contrasts for public consumption ('us = good vs. they = bad'). At the onset of the Gulf War in 1991, George Lakoff circulated a paper showing how the metaphorical presentation of the conflict in terms, notably, of a fairy-tale narrative (a hero rescuing a victim from the power of a villain) not only gave U.S. involvement a veneer of acceptability, but moreover polarized opinion in such a manner as to demonize Saddam Hussein. This genre-crossing between political argumentation and narrative reduction inspired Robert Clark to write: 'The narrativisation of Iraqi actions and questions of truth in representation have become the ground where our democracies either survive or fail. Wars always begin with the stories about the Others.'

A two-valued representation in which 'the bad guys are lumped together' has fostered in the public's mind the politically convenient fiction of a link between the WTC attacks and Saddam Hussein. According to Deborah Tannen, President Bush sought to imply this connection to suggest that when they invaded Iraq, the US went to war with the terrorists who attacked them – an amalgam that reportedly went down well with the public: 'If we like the conclusion, we're much less critical of the logic.' John Mueller is quoted in the same article as saying: 'It's very easy to picture Saddam as a demon. You get a general fuzz going around: people know they don't like al Qaeda, they are horrified by September 11th, they know this guy is a bad guy, and it's not hard to put those things together.'

The second point is that here as elsewhere, responsibility for human preferences can be allocated to divine authority, without much need for further justification: ‘This call of history has come to the right country (...) We do not claim to know all the ways of Providence, yet we can trust in them, placing our confidence in the loving God behind all of life and all of history’. (Bush, State of the Union, 2003).

What can be observed is that these two verbal strategies were combined, and that the two-valued polarities were 'mythified', i.e. given a moral and religious dimension. As in Van Dijk's ideological square, the moral dimension assimilated the polarity us / them with the contrast good / evil, while the religious dimension represented the US role in the contest between good and evil as part of the divine purpose: ‘Freedom and fear are at war. The advance of human freedom -- the great achievement of our time, and the great hope of every time -- now depends on us [...] The course of this conflict is not known, yet its outcome is certain. Freedom and fear, justice and cruelty, have always been at war, and we know that God is not neutral between them’. (Bush, Speech to Joint Session of Congress and the Country, 2001)

The rhetoric skillfully equated God’s and Bush’s definitions of freedom and justice, and thus granted the U.S. the status of an instrument in the implementation of God’s plans for the world. In this respect, it is interesting to note the role played by U.S. evangelicals in the fight against Evil and the preparation of the Second Coming as projected in Lahaye & Jenkins' Apocalyptic Left Behind novels. The links between Iraq, Babylon and the Antichrist figured centrally in the fundamentalist vision of things religious and political, and were exploited by several 'studies' and less serious websites, one of which even produced a bogus prophecy, allegedly from the Quran 9:11 (note the reference!): ‘For it is written that a son of Arabia would awaken a fearsome Eagle. The wrath of the Eagle would be felt throughout the lands of Allah and lo, while some of the people trembled in despair still more rejoiced; for the wrath of the Eagle cleansed the lands of Allah; and there was peace’. (Truthorfiction 2003)

The Quran quote is false. On the other hand, Bush’s quotes from the Bible and hymnals were authentic, but dislocated form their original context, pasted together in misleading manners, or employed in ways which distort their meaning.

In his inaugural address, George W. Bush suggested that 'we are guided by a power larger than ourselves who creates us equal in his image.' This calls for two comments:

1. Divine guidance is a matter of faith, and not necessarily a criticable idea provided one does not project into it one's own desires and aspirations: John Wesley (1746) cautioned that 'the presumptuous, self-deceiving Christian may mistake the voice of his own desire and imagination for the voice of God.' and that the visible 'evidence' of the Spirit resided in its outward 'fruits' (as described in Galatians 5:22 – not in military victories or strengthened strategic positions).

2. The Enlightenment's conviction that all men are born/created equal has found its expression in the Declaration of Independence and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In its religious form (e.g. Galatians 3:28) it undoubtedly underlies Wesley's theology of grace 'for all' willed, but not imposed, by God. Bush's clause 'a power who creates us equal in his image', however (besides the strange choice of tense) introduced a relationship of analogy that has no scriptural counterpart. One easy misreading of the formula (hopefully, not a deliberately induced one) is a form of national self-deification, whereby 'we' are created equal not in, but to the divine image; in Monbiot's words, 'America no longer needs to call upon God; it is God, and those who go abroad to spread the light do so in the name of a celestial domain' (Monbiot, America is a Religion, 2003).

On the first anniversary of the 2001 terrorist attacks, President Bush said at Ellis Island, 'This ideal of America is the hope of all mankind. That hope still lights our way. And the light shines in the darkness. And the darkness has not overcome it.' While the 'glow from a fire that lights the world' has, since John Kennedys inaugural, become a U.S. ideological cliché, the last two sentences are straight out of John's gospel. But in the gospel the light shining in the darkness is the Word of God, and the light is the light of Christ. It is not about America and its values.

In the 2003 State of the Union address, the president evoked an easily recognized and quite famous line from an old gospel hymn. Speaking of America's deepest problems, Bush said: 'The need is great. Yet there's power, wonder-working power, in the goodness and idealism and faith of the American people.' But that is not what the song is about. The hymn says there is "power, power, wonder-working power in the blood of the Lamb'. The hymn is about the power of Christ in salvation, not the power of the American people, or any people, or any country. Bush's citation was a complete misuse.

Could this strategy possibly be intended to fulfill a further purpose? America was – obviously and understandably – traumatized by 9/11, and seeking solace in religion and patriotism, both of which provided a much-needed certainty. George Bush's unambiguous use of terms like 'evildoers' was felt to convey just this sense of strength and certainty (rather than critical reflection), and to make Americans feel there was a moral, and even divine cause to be defended ('We were targeted because we're the brightest beacon for freedom'). It was a politically astute way of rallying Americans around a cause. Talk of a nation chosen by God to set things right in the world certainly made good epideictic rhetoric, intended to reassure and trigger a positive response. It conveyed a sense of unity, it made people 'feel good', gave them a sense of purpose, and was even likely to be expected and approved of by a substantial part of the Christian-conservative electorate.

There are an estimated 90 million evangelical Christians in the US. 40 % of the population are white evangelical Christians, arguably the most important single constituency in the US, a significant proportion of whom have backed the policies and the candidacy a president whose idiom resonated with them as a matter of faith. Of course, 'evangelicals' should not be regarded as one monolithic unit: here as elsewhere, people display different degrees of religious commitment and of religious belief ranging from conservative to moderate, and not all evangelicals adhere to the same values or are sensitive to the same issues.

If, as has been increasingly suspected and suggested, the recourse to religious language was a strategy, it seems to have worked for some, and not for others. Some pastors and their churches on the receiving end declared they would ‘do everything within the law to get Bush re-elected', while others voiced fears that Bush was representing the war on Iraq as a holy crusade, and/or insisted on the constitutional separation between Church and State. But in a race which was expected to be a lot closer than it turned out to be, the evangelical constituency constituted a solid body of political support which helped tilt the scales towards George W. Bush’s victory in the November 2004 presidential elections.

Jean-Pierre van Noppen (ULB).

MangoGem

MangoGem