Résultats de la recherche pour : Younes Johan Van Praet

Revue de presse, 7 septembre

Entretiens

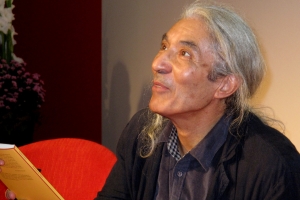

"Dans son nouveau livre, 2084, La fin du monde, Boualem Sansal imagine l'avènement d'un empire planétaire intégriste. L'auteur redoute la montée en puissance de l'islamisme dans une version 'totalitaire et conquérante'" — Boualem Sansal : du totalitarisme de Big Brother à l'islamisme radical (Alexandre Devecchio, Le Figaro)

"S'il a refusé de s'entretenir avec la journaliste du Monde Ariane Chemin, laquelle a pourtant consacré une série bien garnie à l'auteur, Michel Houellebecq s'est lâché dans la presse britannique. Ces mots, c'est au Guardian qu'il les a confiés, interviewé par Angelique Chrisafis" — Houellebecq : «Je suis probablement islamophobe» (P. Sc., Le Soir)

Revue de presse hebdo, 5 septembre

Inde

La semaine dernière, un conseil de village du nord de l’Inde a exigé que deux jeunes filles soient violées collectivement. Si cette décision a suscité l'indignation générale, c'est loin d'être un cas isolé. Les châtiments archaïques de ce type subsistent dans plusieurs régions du monde — Viols collectifs, lapidations, peines capitales… Quand le rite fait justice (Hortense Nicolet, Le Figaro)

Pakistan

Les Zoroastriens sont établis depuis plus d'un millénaire dans le sous-continent indien, mais le vieillissement de la population dans cette communauté aux règles de mariages strictes et une vague d'exil en Occident pourraient y reléguer ces "adorateurs du feu" aux livres d'histoire — Au Pakistan, quel avenir pour adeptes du culte de Zarathoustra ? (Le Vif)

Revue de presse, 4 septembre

Hongrie

"Etre chrétien, c'est 'montrer que l'on est prêt à faire preuve de solidarité', a réagi le président du Conseil européen Donald Tusk, qui reçoit le Premier ministre hongrois" — L'afflux des réfugiés menace l'identité chrétienne de l'Europe, selon Viktor Orban (AFP, Le Soir)

Les récents propos du Premier ministre hongrois Viktor Orban à propos des réfugiés qui sont, selon lui, 'une menace pour l'identité chrétienne en Europe' - suivis de la réaction par téléphone de Jean-Pierre Delville, évêque de Liège et professeur à l'UCL (Aline Gonçalves, Matin Première - RTBF)

Revue de presse, 3 septembre

Belgique

"Charles Michel, Jan Jambon et Bart De Wever sont partis à la rencontre de la communauté juive d'Anvers pour parler sécurité" — Sécurité des Juifs : «Des mesures à la hauteur des menaces», selon De Wever (D.V et M.Bn, Le Soir)

"De Joodse gemeenschap in Antwerpen kreeg bezoek van premier Charles Michel (MR) en minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Jan Jambon (N-VA). Het belangrijkste thema: veiligheid" — Michel : 'Nultolerantie voor antisemitisme' (jvt en Belga, De Standaard)

Austria

Austria has, on the one hand, a strong Catholic tradition and on the other hand, has had long experience in coping legally with religious pluralism, due to its geopolitical position in the center of Europe, which created a multi-confessional society in earlier times. Over the last decades this system has expanded, but has also been subject to multiple challenges from developments which are partly converging and partly conflicting: an on-going secularization, a steady increase in religious pluralisation mainly ensuing from a growing number of Muslim and Orthodox immigrants — as well as Catholics with a foreign cultural background —, new forms of spirituality and a growing public interest in religion.

Belgium

Belgium is historically a Catholic country. A few years after the creation of the State in 1830, more than 99 % of its inhabitants identified themselves as Catholic in a survey of the general population. Only a few Protestant and Jewish communities introduced some religious diversity; yet it was enough for the State to grant public subsidies to those communities alongside the powerful Catholic Church. In XIXth century Belgium, the Catholic Church enjoyed wide authority, supported by an expanding network of Catholic schools and the development of a Catholic political party.

Croatia

Croatia is a predominantly Catholic country in which religion is significantly present in private life as well as in the public sphere, where its role has been subject to debate. According to 2011 Census data, 86.28 % of the population is Catholic, 4.44 % Orthodox, 1.47 % Muslim, 0.34 % Protestant, 0.43 % member of other religious denominations, and 7.03 % non-religious, atheist, “not declared”, agnostic, sceptic, or “unknown”. A comparison with 2001 Census data reveals almost no changes, while a comparison with 1991 Census data shows that major shifts in the confessional structure have taken place, i.e. an increase of the number of Catholics and a decrease of the number of Orthodox, mainly as a result of the disintegration of former Yugoslavia and the war for Croatian independence. Thus the share of Catholics has risen from 76.5 % in 1991 to 87.97 % in 2001, while the share of Orthodox has dropped from 11.1 % in 1991 to 4.42 % in 2011. There has also been a small but significant rise in the share of non-believers, “not declared”, agnostics and “unknown”: from 3.9 % in 1991 to 7.03 % in 2011 (Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Census data).

Denmark

Denmark is predominantly Lutheran. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark has 4.4 million members out of a total population of 5.6 million. It was established in 1849 as part of the first democratic Constitution. The highest Church authority is the government, c.q. the minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs. In many ways it is still a State Church, but it is highly egalitarian and the individual parishes have some power too — hiring all staff, approving of liturgical changes, and acting as keepers of cemeteries...

Estonia

Estonia is a fine example of a European country where secularization and secularity seem to be inherent features of society, and where general indifference concerning religion in all of its aspects prevails (Casanova 2006; Bruce 2002). Indeed it is often considered to be one of the least religious and most secularized societies in an already highly secularized Europe. This image is largely the fruit of the publication of Eurobarometer 2005 poll results that identified Estonia as the least god-believing country in Europe. Consequently, media reports have further strengthened the Estonians’ self-image as the most irreligious nation of the EU (Remmel 2013).

Finland

According to Eurostat (2011), Finland is culturally, ethnically and religiously one of the most homogeneous countries in Europe. This is reflected in its religious landscape: although particularly because of Muslim immigrants and refugees, religious diversity has increased since the 1990’s, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland remains the biggest religious denomination. Nearly three quarters of the Finnish population is a member of the Lutheran Church. Other religious groups cover a bit less than 3 % altogether. The remaining part of the population – more than 20 % – is unaffiliated. Some are atheists or religiously indifferent, whereas there are also people who consider themselves religious or spiritual but are not members of any registered religious community. The most significant change is a decrease in membership of the dominant Church, partly because one can easily resign via a website and partly because the Church is considered conservative on issues relating to same-sex marriage. Membership has gone down from more than 90 % in 1980 to 88 % in 1990, 85 % in 2000, 78 % in 2010 and 73.7 % in 2014.

MangoGem

MangoGem