Résultats de la recherche pour : Gustavo Gomes da Costa

The religious situation in Romania

A country of twenty million Latin-language speaking inhabitants, Romania is situated on the crossroad of different politic, religious and cultural influences. In the Moldavian and the Walachia principalities, the role of the Byzantine, the Ottoman, and the Russian Empires was essential. As for Transylvania, it was influenced by Vienna, Budapest and Rome. Unavoidably, this historic heritage is closely related to the Romanian religious situation.

Estonia

Estonia is a fine example of a European country where secularization and secularity seem to be inherent features of society, and where general indifference concerning religion in all of its aspects prevails (Casanova 2006; Bruce 2002). Indeed it is often considered to be one of the least religious and most secularized societies in an already highly secularized Europe. This image is largely the fruit of the publication of Eurobarometer 2005 poll results that identified Estonia as the least god-believing country in Europe. Consequently, media reports have further strengthened the Estonians’ self-image as the most irreligious nation of the EU (Remmel 2013).

Germany

For some decades now, the nature of the relations between politics and religion in Germany has been the subject of profound mutations that are linked to secularization, to the growing importance of the so-called Konfessionslose, to religious individualization and pluralization and, most importantly, to the ever increasing presence of Islam. These evolutions, which tend to question the bi-confessional protestant-catholic balance that has for long been considered an essential dimension of German collective identity, shake up the representations of a society that has difficulties imagining pluralism and confessional neutrality without any reference to Christianity. Thus public authorities have to find political and legal means of reconciling the protection of freedom of conscience and religion, the principle of State neutrality, and equal treatment of all religious communities.

Hungary

The changing religious situation in Hungary since the fall of communism is the consequence of different trends. The majority of Hungarians identify themselves as Catholic or Protestant. At the same time, traditional churches are struggling to reach large parts of society that are more inclined to uphold individual types of religious attitudes and behaviour. In recent years, increased political influence in the religious field has made the picture even more complex. For centuries, Hungary has been characterized by religious plurality. Besides the predominant Roman Catholic denomination, significant parts of the population belong to the Calvinist and Lutheran Protestant traditions, as well as to the Greek Catholic Church. According to the most recent census (2011), slightly more than half of those reporting about their religious affiliation were Catholic, 16 % were Calvinist and 3 % were Lutheran. Other religions, including traditional ones like Judaism and Orthodoxy as well as new religious movements like the Faith Church (a Hungary-based Pentecostal Church) and the Hare Krishna Movement, all together account for less than 3 %. Recent trends show that the number of unaffiliated people is on the rise, topping at about one fourth of those answering the census question about religiosity in 2011.

Ireland

While Ireland remains a predominantly Catholic society, in recent years the Church has experienced a notable erosion in its authority and power. At the same time, other faiths are growing, and the number of atheists and agnostics is increasing steadily. Ireland is a majority Catholic society. According to the 2011 census, about 84 per cent of the population self-identify as Roman Catholic. At the same time, the Irish religious landscape exhibits considerable diversity. The Orthodox, Hindu, and Pentecostal faiths are the country’s three fastest growing non-Catholic religious traditions. The number of atheists and agnostics has grown by about 320 and 130 per cent respectively in the 2006-2011 span (All-Island Research Observatory (AIRO), PDR Table 35: Percentage and Actual Change in Population by Sex, Religion, Census Year, and Statistic).

Latvia

Up until today, Latvia’s religious landscape has been influenced by ruling ideologies and political systems. When the Republic of Latvia was established in 1918, the Lutherans were active in the country’s political life through the intermediary of their political parties, as did other denominations. In the early 20th century, they were numerically the largest denomination in Latvia, accounting for 55 % of the population. Subsequently, the Lutheran Church suffered heavily during the Soviet occupation: 12 Lutheran pastors were killed in 1940; many others were sent off to Siberia. Repression continued in the 1950s: a significant number of Lutheran churches were deconsecrated and transformed into warehouses, shops, sports halls and clubs. However, the Lutheran Church survived and Lutheran clergy were very active in the anti-Soviet movement during the 1980’s.

Luxembourg

The recent redefinition (2013-2015) of the relationship between the State and so-called recognized religions is currently the major issue animating the religious landscape in Luxembourg. This reform comprises a substantial reduction of the State’s future financial support for religions. It also brings about public recognition of Islam, its representatives having been invited for the first time at the negotiating table. Next to these moves monopolizing media attention, a recent major development seems to go largely unnoticed by the authorities and by public opinion: the staggering success of the Pentecostal ‘megachurches’ originating in the Protestant-evangelical movement.

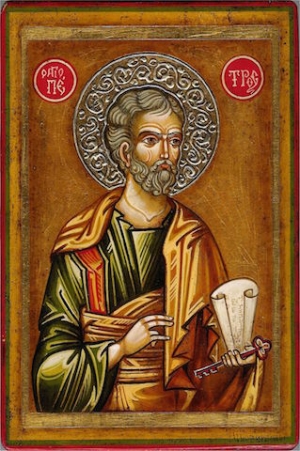

Romania

A country of twenty million Latin-language speaking inhabitants, Romania is situated on the crossroad of different politic, religious and cultural influences. In the Moldavian and the Walachia principalities, the role of the Byzantine, the Ottoman, and the Russian Empires was essential. As for Transylvania, it was influenced by Vienna, Budapest and Rome. Unavoidably, this historic heritage is closely related to the Romanian religious situation. In ancient Moldavian and Walachia principalities, the dominant Church (87 %) is the Orthodox. In Transylvania, different denominations share the believers with the Orthodoxy: Roman Catholicism (5 %), Greek-Catholicism (Uniatism) (1 %) and the Protestantism, or more precisely Calvinism (3 %), Unitarianism (anti-Trinitarians) (0.3 %) and Lutheranism (0.5 %). Roman Catholicism, Calvinism, Unitarianism, and Lutheranism followers are mainly among the Hungarian community.

United Kingdom

A country, which has two established churches, the Church of England and the Church of Scotland, does not seem to be a propitious setting for secularism to flourish. To this point can be added a number of other matters that seem to be inimical to the idea that secularism can prevail in the United Kingdom. There is, for example, the fact that large numbers of State schools in the present day continue to have partly religious foundations, historically once solely Christian or Jewish but now also including the Muslim, Hindu and Sikh faiths. Equally there the fact that one of the established churches, the Church of England, has the legal right, which it exercises, to have bishops and archbishops as members of the House of Lords, one of the two chambers of the United Kingdom Parliament.

Revue de presse, 25 août

Etat islamique

"Les membres du Conseil de sécurité de l'ONU ont entendu lundi les témoignages horribles des persécutions subies par des homosexuels irakiens et syriens aux mains du groupe Etat islamique (EI), lors de la première réunion jamais consacrée aux droits des gays" — Le groupe Etat islamique «chasse les gays un par un» (L. Co. avec AFP, Le Soir)

"Les membres du Conseil de sécurité de l'ONU ont entendu lundi les témoignages horrifiants des persécutions subies par des gays irakiens et syriens aux mains du groupe Etat Islamique, lors d'une première réunion jamais consacrée aux droits des homosexuels" — Réunion "historique" de l'ONU sur les persécutions de l'EI contre les gays (AFP, Le Vif)

MangoGem

MangoGem