Revue de presse, 22 janvier

Arabie saoudite

"Le Grand Mufti d'Arabie saoudite a lancé une fatwa sur ce jeu, qui constituerait 'une perte de temps' et serait contraire à la loi islamique" — Un religieux saoudien lance une fatwa sur les échecs (Yohan Blavignet, Le Figaro)

Qatar

"Un exemplaire du conte de Walt Disney a été retiré de la bibliothèque d'une école. Il contenait des illustrations 'indécentes', selon les parents" — Qatar : des écoliers privés de "Blanche-Neige" pour cause d'"indécence" (AFP, Le Point)

Revue de presse, 21 janvier

France

"Le différend qui oppose le président de l'Observatoire Jean-Louis Bianco et le premier ministre Manuel Valls illustre les clivages qui agitent la gauche au sujet de la laïcité et les limites de cette structure voulue par Jacques Chirac" — Qu'est-ce que l'Observatoire de la laïcité? (Mathilde Siraud, Le Figaro)

"Les propos tenus par le premier ministre lundi soir, reprochant à l'observatoire de la laïcité d'en 'dénaturer la réalité' relancent l'opposition entre les tenants d'une laïcité intransigeante et ceux d'une laïcité conciliante" — Laïcité : s'en tenir à l'adogmatisme ? (Jean-Pierre Veran, Blogs-Mediapart)

Revue de presse, 20 janvier

Pakistan

"Des hommes armés ont ouvert le feu, mercredi 20 janvier, dans l'université Bacha Khan de Charsadda, dans le nord-ouest du Pakistan. Au moins 21 personnes ont été tuées dans l'attaque, selon la police" — Pakistan : les talibans revendiquent l'attaque d'une université (AFP et Reuters, Le Monde)

"La plupart des victimes ont été tuées dans des résidences pour garçons. Les opérations de police sont terminées, annonce le chef des forces de sécurité" — Pakistan : 21 morts dans l'attaque d'une université (AFP, Le Point)

Revue de presse, 19 janvier

Christianisme

"A partir de ce lundi 18 janvier se tient, comme chaque année depuis 1908, la Semaine de prière pour l'unité des chrétiens. Une manifestation majeure du mouvement œcuménique, célébrée par les principales Eglises du monde. Elle a pour but de favoriser, par des moyens spirituels, la pleine unité de tous les chrétiens" — Prier pour l'unité des chrétiens (Yzé Nève, Cathobel)

"Du 17 au 23 janvier, les chrétiens célèbrent la Semaine pour l'unité. De nombreux jeunes s'engagent, mais autrement que leurs aînés, aux côtés de fidèles d'autres confessions" — Ces jeunes qui pratiquent « l'œcuménisme du quotidien » (Loup Besmond de Senneville, La Croix)

Save the date : La Religion dans la Cité à Flagey

ORELA, en collaboration avec Le Soir, la RTBF et Flagey, vous convie à deux journées de débats, de conférences, de concerts, de stand-up, de lectures, les 29 et 30 janvier 2016. Avec la participation de : Jean Baubérot, Dominique Schnapper, Abdennour Bidar, Tariq Ramadan, Guy Haarscher, Marie-Claire Foblets, Hervé Hasquin, Olivier Roy, Jean-Claude Bologne, Jean-Loup Amselle, Nadia Geerts, Edouard Delruelle, Faouzia Charfi, Eric de Beukelaer, Bernard Foccroulle, Abdelmajid Charfi, Gilbert Achcar, François De Smet, Jean-Luc Pouthier, Jean Leclercq, Jozef De Kesel, Henri Bartholomeeusen… ainsi que Abd al Malik, Mousta Largo, Sam Touzani, Ismaël Saidi, Samia Orosemane, Pierre Kroll, Richard Ruben, Zidani, Ben Hamidou, Kody, Alex Vizorek, Laurence Bibot, Nathalie Uffner, Thomas Gunzig, Valérie Bauchau et Laurent Capelluto...

Plus d'infos sur : www.lareligiondanslacite.be

Revue de presse, 18 janvier

Dialogue interreligieux

"Le pape François a appelé dimanche les trois religions monothéistes -christianisme, islam et judaïsme-- à rejeter toute violence qui est 'en contradiction' avec elles, lors de sa première visite à la synagogue de Rome" — Le pape François à la synagogue de Rome: "La violence en contradiction avec les 3 religions monothéistes" (AFP, La Libre)

"La troisième visite d'un pape à la Synagogue de Rome a été marquée par un appel commun des juifs et des chrétiens à rejeter toute violence perpétrée au nom de Dieu" — «La violence de homme sur l'homme est en contradiction avec toute religion digne de ce nom» (Jean-Marie Guénois, Le Figaro)

Revue de presse hebdo, 16 janvier

Burkina Faso

Le ministre de l'Intérieur burkinabé a annoncé qu'au moins 22 personnes étaient mortes dans l'attaque terroriste de cette nuit. Quelque 126 personnes, dont 33 blessées, ont en revanche été libérées après l'attaque de cette nuit, revendiquée par Aqmi. Trois terroristes ont été tués, a-t-on précisé. Les assauts sont terminés sur l’hôtel Splendid et le restaurant Cappuccino, mais un assaut est en cours sur un autre hôtel — Burkina : au moins 22 morts, trois jihadistes tués, un assaut en cours (Libération)

L'attaque a été revendiquée par le groupe djihadiste Aqmi, qui l'a attribuée au groupe islamiste al-Mourabitoune du chef djihadiste Mokhtar Belmokhtar, selon SITE, une organisation américaine qui surveille les sites internet islamistes. Des «frères» du «bataillon Al-Mourabitoune ont fait irruption dans un restaurant des plus grands hôtels de la capitale du Burkina Faso, et sont maintenant retranchés et les combats continuent avec les ennemis de la religion», indique le message d'Aqmi — Aqmi revendique l'attaque meurtrière contre un hôtel de Ouagadougou (Le Figaro)

Revue de presse, 15 janvier

France

"Malgré les bilans annuels, il est difficile d'avoir une vue d'ensemble des actes antisémites en France. Après la nouvelle agression survenue à Marseille, le point sur les chiffres connus, leur évolution et leurs limites" — Actes antisémites en France : des hausses souvent liées à l'actualité (Blandine Le Cain, Le Figaro)

"Même si les Juifs s'inquiètent toujours pour leur sécurité, les mouvements de solidarité qui ont suivi janvier 2015 dans toute la France les ont rassurés" — Depuis la tragédie de l'Hyper Cacher, la communauté juive se sent moins seule (Bernadette Sauvaget, Libération)

Revue de presse, 14 janvier

Judaïsme

"Le port de la kippa n'est pas une obligation religieuse mais une tradition, devenue un symbole de ralliement de la communauté juive" — Pourquoi les Juifs portent la kippa (Eugénie Bastié, Le Figaro)

"Après l'agression à l'arme blanche, lundi 11 janvier, d'un enseignant marseillais juif par un lycéen, le président du consistoire israélite de Marseille, Zvi Ammar, a conseillé aux juifs 'd'enlever leur kippa dans cette période troublée'. Une déclaration qui suscite un vif débat, la kippa étant devenue le symbole de l'homme juif" — Cinq questions sur la kippa (Perrine Mourterde, Le Monde)

Revue de presse, 13 janvier

Turquie

"L'auteur de l'attentat-suicide qui a tué mardi dans le coeur historique d'Istanbul au moins 10 personnes, dont 8 Allemands, est un jihadiste du groupe Etat islamique (EI), a affirmé le Premier ministre islamo-conservateur turc Ahmet Davutoglu" — Turquie : L'auteur de l'attentat à Istanbul est un jihadiste de l'Etat islamique (AFP, Le Vif)

"Un 'kamikaze' s'est fait exploser au milieu de touristes. Dix étrangers, dont au moins huit Allemands et un Péruvien, ont été tués" — Attentat à Istanbul : trois djihadistes arrêtés (Belga, Le Soir)

Plus...

Revue de presse, 12 janvier

Sénégal

"Le mouvement religieux Sukyo Mahikari, fondé en 1959 par un officier japonais, s'est discrètement implanté ces dernières années en Afrique de l'Ouest. Ses adeptes sont convaincus de l'existence d'une lumière divine capable de guérir les maux physiques et psychiques. Au Sénégal, on compte un millier d'initiés. Comment expliquer l'attrait même timide pour ce mouvement religieux dans un pays à 90 % musulman, considéré par beaucoup comme une secte ?" — Quand une religion japonaise fait son nid au Sénégal (Coumba Kane, Le Monde)

Somaliland

"Au Somaliland, petit pays autoproclamé indépendant du reste de la Somalie, bordé de la région du Puntland, de l'Ethiopie et de Djibouti, le conservatisme religieux rogne parfois les plaisirs du quotidien. Le Golfe est à moins de 200 km à vol d'oiseau, de l'autre côté de la mer. Une approche rigoriste de l'islam – salafisme ou wahhabisme, dit-on à voix basse en mélangeant les deux courants – étend son influence un peu plus chaque jour" — Au Somaliland, un islam rigoriste gagne du terrain (Vincent Defait, Le Monde)

Revue de presse, 11 janvier

Allemagne

"Le scandale des multiples agressions de femmes lors du Nouvel An à Cologne n'en finit pas de secouer l'Allemagne, et plusieurs manifestations en réaction à ces faits se sont déroulées samedi 9 janvier dans la ville. L'un de ces rassemblements, à l'appel du mouvement islamophone et xénophobe Pegida, a donné lieu à des heurts avec la police" — Heurts entre manifestants d'extrême droite et policiers à Cologne (AFP, Le Monde)

"Des centaines d'enfants du fameux chœur de la cathédrale de Ratisbonne en Bavière ont été victimes dans l'après-guerre de sévices et abus sexuels. Pendant trente ans, de 1964 à 1994, Georg Ratzinger, frère du pape émérite Benoît XVI, a été maître de chapelle du chœur, mais non pas de l'internat où les choristes ont été maltraités" — Allemagne : sévices et abus sexuels contre des centaines de choristes de la cathédrale de Ratisbonne (Marcel Linden, La Libre)

Revue de presse, 9-10 janvier

France

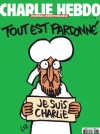

"Samedi 9 et dimanche 10 janvier, les 2 500 lieux de culte que compte la France sont appelés à participer à une opération « portes ouvertes ». Lancée un an après les attentats de janvier, l’initiative du Conseil français du culte musulman (CFCM) vise à « créer un espace d’échange et de convivialité avec nos compatriotes non musulmans », explique Anouar Kbibeche, son président" — Opération portes ouvertes dans les mosquées (Julien Pascual, Le Monde)

"Un an après les attentats contre Charlie hebdo et contre l’Hyper Cacher de Vincennes, le Conseil français du culte musulman (CFCM) organise une opération « portes ouvertes » pour défendre un islam de « concorde »" — En France, les mosquées ouvrent leurs portes pour mettre en avant les « vraies valeurs » de l’islam (La Croix)

Revue de presse, 8 janvier

France

"Un homme a été abattu par les policiers, jeudi 7 janvier, vers 11 h 30, alors qu'il tentait d'entrer dans un commissariat de police du quartier de Barbès, dans 18e arrondissement de Paris" — L'homme tué devant le commissariat de Barbès a été identifié (AFP, Le Monde)

"Répondant à un appel lancé au lendemain de violences à Ajaccio, plusieurs mosquées ouvriront leurs portes au public les 9 et 10 janvier. Le ministre de l'intérieur, Bernard Cazeneuve se rendra à la mosquée de Saint-Ouen-l'Aumône (Val-d'Oise)" — Les mosquées ouvrent leurs portes pour lutter contre les préjugés (Anne-Bénédicte Hoffner, La Croix)

"Il y a un an, la rédaction de Charlie Hebdo était la cible de terroristes. Avec elle, c'est la liberté d'expression qui était visée. Caroline Fourest, journaliste, essayiste et polémiste française, était l'invitée de Matin Première ce jeudi. Celle qui a travaillé un temps chez Charlie Hebdo analyse les suites de cette attaque et les leçons qui en ont, ou pas, été retenues...." — "Si ça froisse les bigots, ça signifie que Charlie est encore en vie" (J.C., RTBF Info)

MangoGem

MangoGem