Revue de presse, 7 septembre

Entretiens

"Dans son nouveau livre, 2084, La fin du monde, Boualem Sansal imagine l'avènement d'un empire planétaire intégriste. L'auteur redoute la montée en puissance de l'islamisme dans une version 'totalitaire et conquérante'" — Boualem Sansal : du totalitarisme de Big Brother à l'islamisme radical (Alexandre Devecchio, Le Figaro)

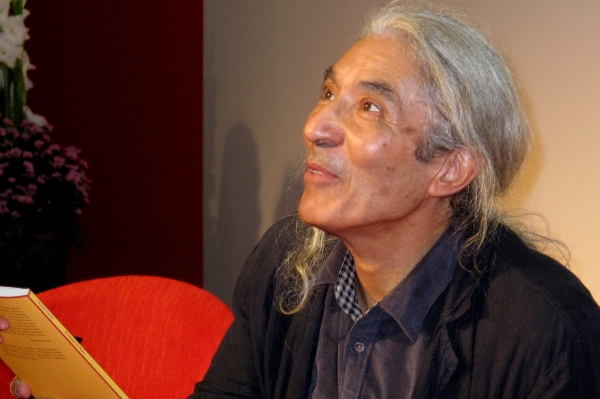

"S'il a refusé de s'entretenir avec la journaliste du Monde Ariane Chemin, laquelle a pourtant consacré une série bien garnie à l'auteur, Michel Houellebecq s'est lâché dans la presse britannique. Ces mots, c'est au Guardian qu'il les a confiés, interviewé par Angelique Chrisafis" — Houellebecq : «Je suis probablement islamophobe» (P. Sc., Le Soir)

Revue de presse hebdo, 5 septembre

Inde

La semaine dernière, un conseil de village du nord de l’Inde a exigé que deux jeunes filles soient violées collectivement. Si cette décision a suscité l'indignation générale, c'est loin d'être un cas isolé. Les châtiments archaïques de ce type subsistent dans plusieurs régions du monde — Viols collectifs, lapidations, peines capitales… Quand le rite fait justice (Hortense Nicolet, Le Figaro)

Pakistan

Les Zoroastriens sont établis depuis plus d'un millénaire dans le sous-continent indien, mais le vieillissement de la population dans cette communauté aux règles de mariages strictes et une vague d'exil en Occident pourraient y reléguer ces "adorateurs du feu" aux livres d'histoire — Au Pakistan, quel avenir pour adeptes du culte de Zarathoustra ? (Le Vif)

Revue de presse, 4 septembre

Hongrie

"Etre chrétien, c'est 'montrer que l'on est prêt à faire preuve de solidarité', a réagi le président du Conseil européen Donald Tusk, qui reçoit le Premier ministre hongrois" — L'afflux des réfugiés menace l'identité chrétienne de l'Europe, selon Viktor Orban (AFP, Le Soir)

Les récents propos du Premier ministre hongrois Viktor Orban à propos des réfugiés qui sont, selon lui, 'une menace pour l'identité chrétienne en Europe' - suivis de la réaction par téléphone de Jean-Pierre Delville, évêque de Liège et professeur à l'UCL (Aline Gonçalves, Matin Première - RTBF)

L'Observatoire des Religions et de la Laïcité (ORELA) de l'Université libre de Bruxelles fait paraître son troisième rapport sur l'état des religions et de la laïcité en Belgique, portant sur l'année 2014. Fort de près de 100 pages, ce rapport propose des commentaires et analyses relatifs à ce qui a fait l'actualité des religions et de la laïcité en Belgique l'an dernier. Il aborde le domaine des rapports entre religion et société comme celui des relations entre l'Etat et les cultes, et ce dans un contexte marqué de forte médiatisation du religieux, de peurs autour de l'islam, de recrudescence de l'antisémitisme, de débats sur des questions éthiques, entre sécularisation de la société et retour institutionnel des religions. Il met en particulier en évidence la diversité culturelle et convictionnelle que l'on rencontre dans la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale, contrastant souvent avec la situation connue dans les autres Régions du pays.

Revue de presse, 3 septembre

Belgique

"Charles Michel, Jan Jambon et Bart De Wever sont partis à la rencontre de la communauté juive d'Anvers pour parler sécurité" — Sécurité des Juifs : «Des mesures à la hauteur des menaces», selon De Wever (D.V et M.Bn, Le Soir)

"De Joodse gemeenschap in Antwerpen kreeg bezoek van premier Charles Michel (MR) en minister van Binnenlandse Zaken Jan Jambon (N-VA). Het belangrijkste thema: veiligheid" — Michel : 'Nultolerantie voor antisemitisme' (jvt en Belga, De Standaard)

Austria has, on the one hand, a strong Catholic tradition and on the other hand, has had long experience in coping legally with religious pluralism, due to its geopolitical position in the center of Europe, which created a multi-confessional society in earlier times. Over the last decades this system has expanded, but has also been subject to multiple challenges from developments which are partly converging and partly conflicting: an on-going secularization, a steady increase in religious pluralisation mainly ensuing from a growing number of Muslim and Orthodox immigrants — as well as Catholics with a foreign cultural background —, new forms of spirituality and a growing public interest in religion.

Belgium is historically a Catholic country. A few years after the creation of the State in 1830, more than 99 % of its inhabitants identified themselves as Catholic in a survey of the general population. Only a few Protestant and Jewish communities introduced some religious diversity; yet it was enough for the State to grant public subsidies to those communities alongside the powerful Catholic Church. In XIXth century Belgium, the Catholic Church enjoyed wide authority, supported by an expanding network of Catholic schools and the development of a Catholic political party.

Baptized by Byzantium in 865, Bulgarians adopted the Byzantine Christian tradition known as Eastern Orthodoxy. Muslims constitute the second most significant religious community, thanks to the spread, in the fourteenth century, of Islam during the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans. At the end of World War II, 85 % of Bulgarian citizens were Orthodox and 13 % were Muslim. Tiny congregations of Catholics, Protestants, Jews, etc. also exist. Even though they were suppressed under communism, these religious denominations very quickly returned to the public square once the Iron Curtain had fallen, a tendency which was also stimulated by the 1991 Constitution, which proclaimed full-scale religious freedom.

Croatia is a predominantly Catholic country in which religion is significantly present in private life as well as in the public sphere, where its role has been subject to debate. According to 2011 Census data, 86.28 % of the population is Catholic, 4.44 % Orthodox, 1.47 % Muslim, 0.34 % Protestant, 0.43 % member of other religious denominations, and 7.03 % non-religious, atheist, “not declared”, agnostic, sceptic, or “unknown”. A comparison with 2001 Census data reveals almost no changes, while a comparison with 1991 Census data shows that major shifts in the confessional structure have taken place, i.e. an increase of the number of Catholics and a decrease of the number of Orthodox, mainly as a result of the disintegration of former Yugoslavia and the war for Croatian independence. Thus the share of Catholics has risen from 76.5 % in 1991 to 87.97 % in 2001, while the share of Orthodox has dropped from 11.1 % in 1991 to 4.42 % in 2011. There has also been a small but significant rise in the share of non-believers, “not declared”, agnostics and “unknown”: from 3.9 % in 1991 to 7.03 % in 2011 (Croatian Bureau of Statistics, Census data).

After 1974, the Republic of Cyprus became an overwhelmingly Orthodox country. Institutionally, the Church is completely outside of the State’s control. The Church of Cyprus’ multifaceted and multiple activities have an impact upon the island’s economic and cultural life, while the Church is also active in international forums. Since 2006, the Church has acquired a full Synod and hence it has become fully autonomous. The ecclesiastical institutions were hurt extensively by the 2008 crisis. However, they have been able to offer a multitude of charitable aid to the people. By European standards, the extent of secularization in the Republic remains low.

Plus...

The history of Christianity in Czech lands goes back to the 9th century when prince Bořivoj I. was baptized. In the early 15th century, Jan Hus, a reformist priest and predecessor of the Protestant movement, was burned for heresy against Catholic doctrine. This initiated the Hussite movement (also known as the Czech Reformation) that introduced Protestantism into Czech lands. After 1620, the Habsburg-led Counter-Reformation strived for the suppression of Protestantism and the (largely successful) re-Catholization of the Czech population. From the late 18th century on, more space was opened for Protestant denominations; however, Catholicism remained the dominant religion in Czech lands.

Denmark is predominantly Lutheran. The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark has 4.4 million members out of a total population of 5.6 million. It was established in 1849 as part of the first democratic Constitution. The highest Church authority is the government, c.q. the minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs. In many ways it is still a State Church, but it is highly egalitarian and the individual parishes have some power too — hiring all staff, approving of liturgical changes, and acting as keepers of cemeteries...

Estonia is a fine example of a European country where secularization and secularity seem to be inherent features of society, and where general indifference concerning religion in all of its aspects prevails (Casanova 2006; Bruce 2002). Indeed it is often considered to be one of the least religious and most secularized societies in an already highly secularized Europe. This image is largely the fruit of the publication of Eurobarometer 2005 poll results that identified Estonia as the least god-believing country in Europe. Consequently, media reports have further strengthened the Estonians’ self-image as the most irreligious nation of the EU (Remmel 2013).

According to Eurostat (2011), Finland is culturally, ethnically and religiously one of the most homogeneous countries in Europe. This is reflected in its religious landscape: although particularly because of Muslim immigrants and refugees, religious diversity has increased since the 1990’s, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland remains the biggest religious denomination. Nearly three quarters of the Finnish population is a member of the Lutheran Church. Other religious groups cover a bit less than 3 % altogether. The remaining part of the population – more than 20 % – is unaffiliated. Some are atheists or religiously indifferent, whereas there are also people who consider themselves religious or spiritual but are not members of any registered religious community. The most significant change is a decrease in membership of the dominant Church, partly because one can easily resign via a website and partly because the Church is considered conservative on issues relating to same-sex marriage. Membership has gone down from more than 90 % in 1980 to 88 % in 1990, 85 % in 2000, 78 % in 2010 and 73.7 % in 2014.

MangoGem

MangoGem