Afficher les éléments par tag : Methodism

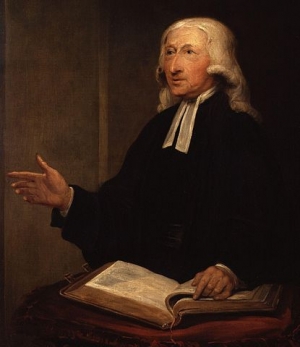

The Early Methodist Revival from a Discourse Perspective

In a number of twentieth-century critiques of Methodism (and notably in E.P. Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class), John Wesley’s discourse has been represented as an instrument in the conversion of the factory proletariat to the industrial work ethic, symptomatic of an emerging ideological paradigm heavily conditioned by the demands of increasing industrialization. While the data adopted as evidence by the critics are authentic, an analysis of the discourse in context reveals that not only have the instances of Methodist discourse been selected and combined to tie in with a particular reading of reality – religion as the opiate of the people – but also that the value judgment fostered by this partial representation has been applied indiscriminately to Methodism as a whole, with blatant disregard for the positive transforming power it exerted both on individuals and on society.

Informations supplémentaires

- Auteur Jean Pierre van Noppen

God in George W. Bush’s Rhetoric

As a matter of intellectual honesty, the use made of Scripture must remain faithful to the original text and intention (inasmuch as these may be retraced). At the point where religious language comes to be fraught with ideology (or vice versa), the emerging discipline of Critical Discourse Analysis may prove useful inasmuch as it (re)places instances of language within their full co-text, con-text and inter-text and seeks to denounce cases of manipulation wherein texts are read according to a system or set of values altogether extraneous to it, or alienated from their original meaning or purpose.

I would like to illustrate this point by means of the case example of George W. Bush's recourse of religious language and categories to justify (notably) U.S. foreign policy and beyond that, to serve his own electoral purposes.

Informations supplémentaires

- Auteur Jean Pierre van Noppen

MangoGem

MangoGem